For years, London’s orbital railways had been one of the capital’s most neglected transport assets with poor and unreliable services serving run down stations. All that changed following devolution of an initial batch of services (the North and West London Lines, the Gospel Oak to Barking Line and the Euston to Watford service) to Transport for London, with a 32% increase in patronage in the first year alone.

This dramatic increase in use was due to TfL’s Year One programme to rebrand the network as London Overground operating to much more demanding standards. The template included combining the first roll out of smart ticketing on the UK rail network with the integration of fares with TfL’s bus and Tube services, saving passengers time and money. Poor perceptions of security and customer service were addressed by deep cleaning stations and staffing them from first train to last. Customer information systems were upgraded and multi-modal information provided.

The relatively low costs of making these improvements was soon justified by the increased patronage as well as a dramatic fall in fare evasion from 13% to 2%.

Some major improvements needed no investment at all. Industry-first contractual measures focused TfL’s new train operator on running services to precise schedules. The number of delayed trains fell by 11%.

London Overground has had a transformative effect on some of the places which were poorly served by rail before.

Two years later, patronage had grown by 51%, stimulated by improvements in punctuality, further station renovations and a new train fleet which saw services lengthened from three to four carriages. However, demand was still a long way from being met. In 2011, a major infrastructure upgrade raised frequencies from six to eight trains per hour on the core Willesden-Stratford section and from two to four trains per hour on the Gospel Oak-Barking branch. A further surge in use followed. In less than four years, the Overground’s patronage had doubled.

TfL’s integrated understanding of the city’s transport, economic and social needs meant demand that had not been envisaged by central Government and private train operators was recognised, planned for and exceeded. TfL’s backing for the Overground was designed to relieve pressure on bus and underground routes by attracting passengers who had rejected the poor quality services which central Government had previously been responsible for, whilst also supporting housing and employment growth areas designated in the Mayor’s London Plan.

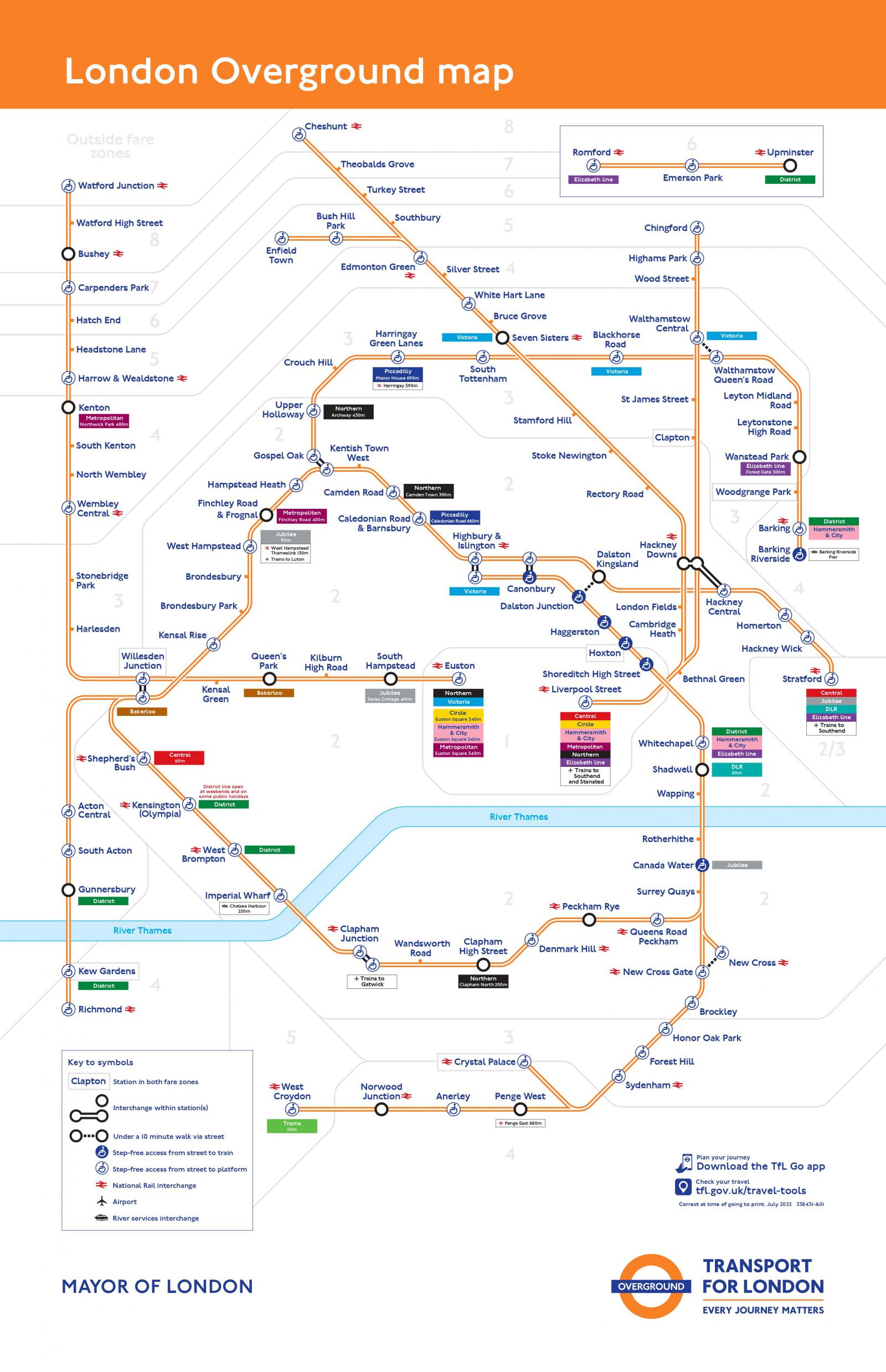

Overhauling the first batch of devolved services was just the start. On the day services transferred to TfL, then London Mayor Ken Livingstone reiterated his intention to integrate the North and West London lines into a more ambitious orbital railway around London. This was completed in 2012 with further routes added to Enfield, Cheshunt and Chingford (as well as Romford to Upminster) added in 2015.

London Overground has had a transformative effect on some of the places which were poorly served by rail before. For example convenient travel options were now available from some of East London’s most deprived neighbourhoods to employment hotspots including financial districts and major hospitals. It opened new career prospects for unskilled and semi-skilled workers, and provided the support staff necessary to stimulate the creation of high value jobs.

Expansion of the network continues to be driven by policies in the London Plan to increase housing supply and capture planning gain.

No other UK railway has seen such dramatic growth, or catered for it so effectively.