Coronavirus and decarbonising transport: How compatible are they?

In late March, our transport landscape changed in a way that none of us could ever have imagined as the COVID-19 outbreak and nationwide lockdown measures lead to a dramatic drop off in movement in the UK. In April 2020, mobility - the extent to which people are moving beyond their home - dropped to 15% of normal levels. This reduction in travel will affect our efforts to reduce emissions from transport. So, rather coincidently, just days after the lockdown was imposed, the Department for Transport published its draft decarbonisation plan, setting out how transport should meet the UK’s target of Net Zero carbon emissions by 2050. The Transport Decarbonisation Plan was widely welcomed across the sector for its strong ambition and six clear strategic priorities:

- Accelerating modal shift to public and active transport

- Decarbonisation of road vehicles

- Decarbonising how we get our goods

- Place-based solutions

- UK as a hub for green transport technology and innovation

- Reducing carbon in a global economy

But the world looks very different in the context of COVID-19. How will the pandemic shape our view of decarbonising transport and what will it mean for sustainable transport going forward? Let’s take each of these strategic priorities in turn and look at them through this new lens.

Accelerating modal shift to public and active transport

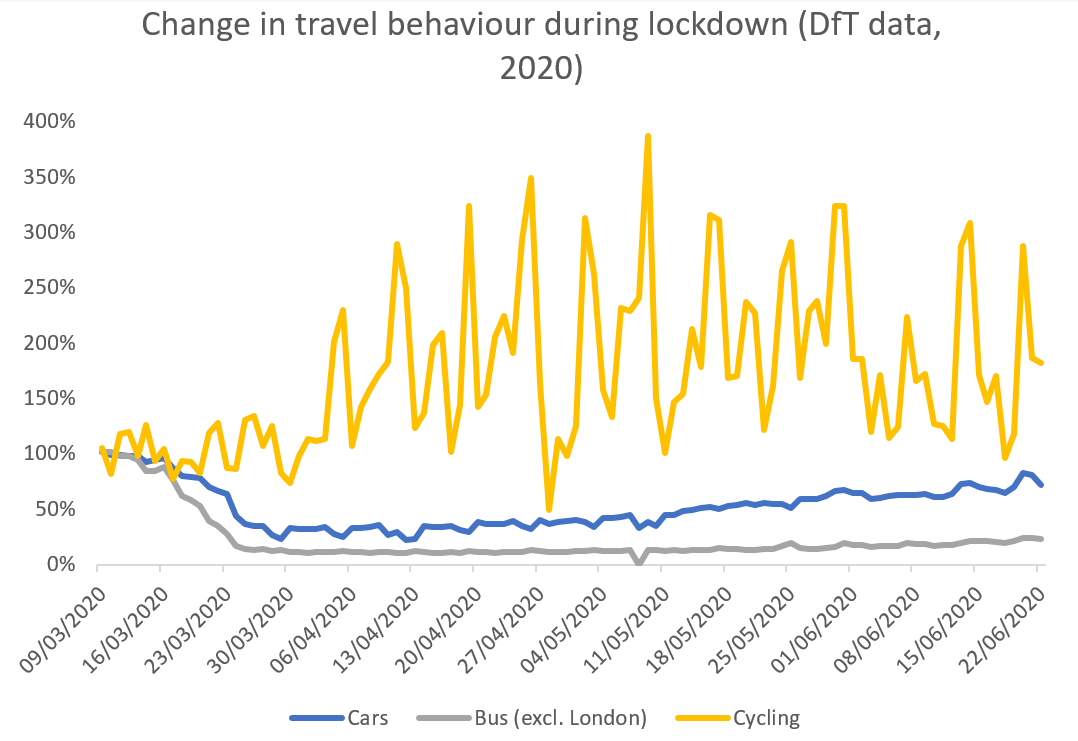

This priority has seen mixed results as a result of lockdown measures: active travel has seen huge increases, with cycling rates in the week at 165% of pre-lockdown levels on average in the week and at 265% at the weekend during May and June, see the graph below (cycling rates are more variable due to weather conditions). In London, Santander Cycles has seen its busiest ever day (on a normal working day) on Wednesday 24 June, with 51,938 hires, and an additional 1,700 bikes and eight new docking stations are being added to the scheme. There have even been reports of shops selling out of bikes. However, public transport ridership has fallen off a cliff, typically less than 20% of pre-lockdown levels, with passengers being told to stay away unless their journey is essential in order to maintain social distancing.  Clearly public transport needs to provide a service for those key workers making essential journeys and they must be prioritised while social distancing restrictions are in place. But it is unclear how and when passengers might be encouraged to return, and if people will have the confidence to do so. The Government has allocated funding to emergency measures to support walking and cycling, including delivering pop-up cycle lanes to help people travel while public transport is less available. However, the money has been slow to arrive, and there are real concerns that people will return to their cars as lockdown is eased, with the negative consequences this has for carbon emissions, as well as air quality and road safety. Car use is already creeping up, we need to maintain the shifts people have made during this period, including working from home, shopping more locally and choosing active travel, in order to lock in the benefits for decarbonisation.

Clearly public transport needs to provide a service for those key workers making essential journeys and they must be prioritised while social distancing restrictions are in place. But it is unclear how and when passengers might be encouraged to return, and if people will have the confidence to do so. The Government has allocated funding to emergency measures to support walking and cycling, including delivering pop-up cycle lanes to help people travel while public transport is less available. However, the money has been slow to arrive, and there are real concerns that people will return to their cars as lockdown is eased, with the negative consequences this has for carbon emissions, as well as air quality and road safety. Car use is already creeping up, we need to maintain the shifts people have made during this period, including working from home, shopping more locally and choosing active travel, in order to lock in the benefits for decarbonisation.

Decarbonisation of road vehicles

As shown above, people are returning to their cars as lockdown measures are eased, in part due to restrictions on public transport use. We need a concerted effort to ensure that road vehicles no longer contribute to climate change, and this is a key priority for the decarbonisation plan. There is a movement building behind the idea of a green recovery, and the electrification of road transport vehicles should be a key part of that. Whether it’s the installation of charging infrastructure or positioning the UK as a global leading in the production of electric vehicles, decarbonisation of road transport presents a real economic opportunity, as well as a key pillar to meeting the 2050 Net Zero target.

Decarbonising how we get our goods

Decarbonisation of freight is a tricky problem. Alternative fuels are not readily available for heavy goods and we have become ever more reliant on white vans to deliver our online packages. However, there are a number of options that can help, from moving more goods by freight and rail to supporting low emission last mile solutions. During lockdown, many of use have been ordering goods online, which often turn up in the ever increasing fleet of white vans driven by gig economy workers. This is problematic in a number of ways, from worker’s rights to the air quality and carbon emission impacts of fleets of diesel vans. There are shining examples of low emission distribution activities, including Gnewt, who use electric vehicles to conduct last mile deliveries and cargo bike solutions. We highlighted a number of these in our report ‘White van cities’. But we need to do more, including support for low emission last mile solutions, R&D for decarbonising larger freight operations and examining options for efficiency such as consolidation centres.

Place-based solutions

Locally-led solutions to a range of policy challenges, including decarbonisation of our cities and enhancing climate resilience, can deliver greater positive outcome for our places. City-led projects have installed green roofs and walls on public buildings and transport infrastructure, used former transport infrastructure to create urban green spaces, and installed renewable energy across transport assets, from interchanges to bus garages. Our 2019 report Making the connections on climate gathered a number of these examples together, from the UK and abroad. Further devolution of powers and funding to enable local areas to develop place-based approaches to decarbonisation and enhanced resilience could accelerate the transition to a low carbon future.

UK as a hub for green transport technology and innovation and reducing carbon in a global economy

These two can be looked at together because, by investing in green transport technology and innovation, we can contribute to the decarbonisation of the global economy. Economic stimulus will be key in the UK’s recovery from the Covid-19 crisis and construction and manufacturing look set to be at the heart of this. But in order to secure a recovery that is compatible with our 2050 Net Zero targets, we need to ensure that we are investing in green projects and manufacturing the technology that the UK and the world will need in order to transition to a low carbon economy. Positioning the UK as a leader in the development and manufacture of green vehicles and other low carbon technologies can be a part of this ‘Green Recovery’. For example, the West Midlands Combined Authority has outlined how it plans to create green manufacturing jobs, as part of its £3.2 billion economic recovery strategy, with a £614 million investment package, including investing £250 million towards a gigafactory producing batteries. We should continue to work with colleagues within Europe and the rest of the world, even as we leave the European Union, because the climate crisis is global, carbon does not respect boarders, and we must collaborate with nations across the world to truly address this crisis. And we can learn from how cities and countries worldwide are tackling the challenges that they face in decarbonising transport and their wider urban environments. There is no doubt that the recovery from the Covid-19 crisis and the resulting economic consequences represents a huge challenge for the UK, the scale of which remains uncertain. However, despite initial estimates of emission reductions of 8% in 2020 compared to 2019, the climate crisis has not gone away. The need to decarbonise our transport system, as part of the wider target to achieve Net Zero carbon emissions by 2050, is still as pressing as it ever was. The draft transport decarbonisation plan sets out a strategy for doing this: we now need to see serious and rapid action as part of a green recovery plan for the coming months and years.

Clare Linton is Policy and Research Advisor at the Urban Transport Group